From the time of Greco-Roman Empire to the Middle Ages, there was very little advancement in medicine. The works of Hippocrates remained dominant, and the main changes in orthopaedics were in amputation.

Living in the 21st century, it is horrific to consider amputation without anaesthesia. Who can forget that scene when Judah Ben Hur confronts Messala after the chariot race, Messala’s legs totally destroyed, his arms chained so the amputation can begin? Or the horror on Scarlett O’Hara’s face (and the world-weary despair of the doctor) as she watches him perform an amputation.

Initially amputation was performed largely as a last resort for gangrene. Aulus Celsus, born around 25 BC, is remembered by his De Medicina, which remains one of the best sources of medical knowledge in the Roman world. Unlike amputations performed up to that time, Celsus described cutting through healthy tissue, and ligating vessels to stop haemorrhage.

“…it is better that some of the sound part should be cut away than that any of the diseased part be left behind. When the bone is reached, the sound flesh is drawn back from the bone and undercut from around it, so that in that part also some bone is bared… (the wound) is to be covered with lint; and over that a sponge soaked in vinegar is to be bandaged on.”

Personally, I’m grateful for anaesthesia.

Until the late Middle Ages there was little change in technique, other than using cautery and hot oil to prevent bleeding. Once more, it took the casualties of war to lead to further developments. By the 13-14th C gunpowder had arrived in Europe, causing significant devastation on the battlefield, including a dramatic increase in the number of amputations.

Ambroise Paré (1510 – 1590), a French army surgeon, rose to eminence as the King’s surgeon, serving four monarchs: Henri II, Francis II, Charles IX and Henri III. He reintroduced the use of ligature rather than cautery, and designed prostheses for both upper and lower limbs (made from iron). He designed an artificial hand called “le petit Lorrain” which had a fixed thumb but spring-loaded movable fingers. His above-knee prosthesis had a movable knee joint, via a thong running to the hip. He also designed a corset to correct scoliosis, and a boot for clubfoot.

Known for his humility, Paré once remarked: “Je le pansai, Dieu le guérit,” (I bandaged him, God healed him). As a consequence of personal experience, Paré wrote widely on the management of trauma. His 1545 Method of Treating Wounds describes how, lacking boiling oil to put on amputated limbs, he instead used a mixture containing rose oil (which contains the mild disinfectant phenol). To his surprise, these patients had a better recovery to those treated with boiling oil.

Unfortunately, it took the Napoleonic wars to lead to more advancements in orthopaedics.

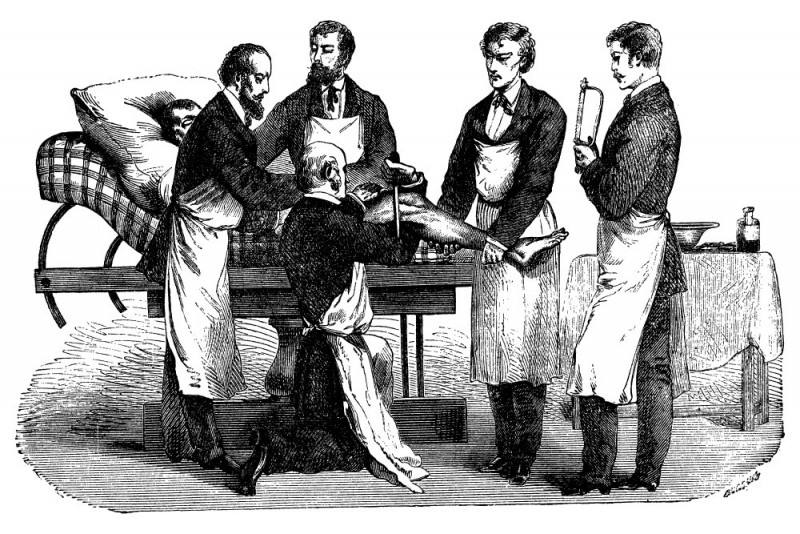

During the 19th century, the discovery of chloroform and ether for anaesthesia, plus improved anti-septic techniques, led to further advances in amputation. Limbs could be removed cleanly and, with the patient anaesthetised, the time could be taken time to ligate (or seal) blood vessels so haemorrhage could be controlled.

As more people survived these procedures, prosthetic development rapidly improved. For example, by the end of WWII, muscle flaps were retained over amputated stumps so that a patient’s own muscle could be used to move the prosthetic limb.

Since then, the use of modern plastics and carbon-fibres in these prosthetics, along with electronic technologies which can adapt to different tasks, mean today’s prosthetics are more personalised to individual needs. Athletes are an obvious example, but even those amputees with less athletic skill may now have multiple limbs, each designed for a different use.

Understanding of pain pathways and syndromes has dramatically improved pain management post amputation. As a result of these advances, amputees today have better function, mobility and quality of life than could ever have been dreamt of during those first crude amputations performed by our ancestors.

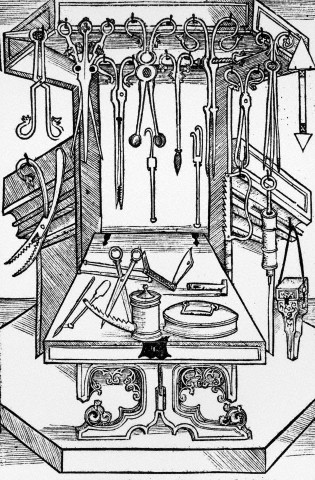

Woodcut Print of Assorted Medieval Medical Tools

ca. 15th-16th century — Image by © Stapleton Collection/Corbis

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.